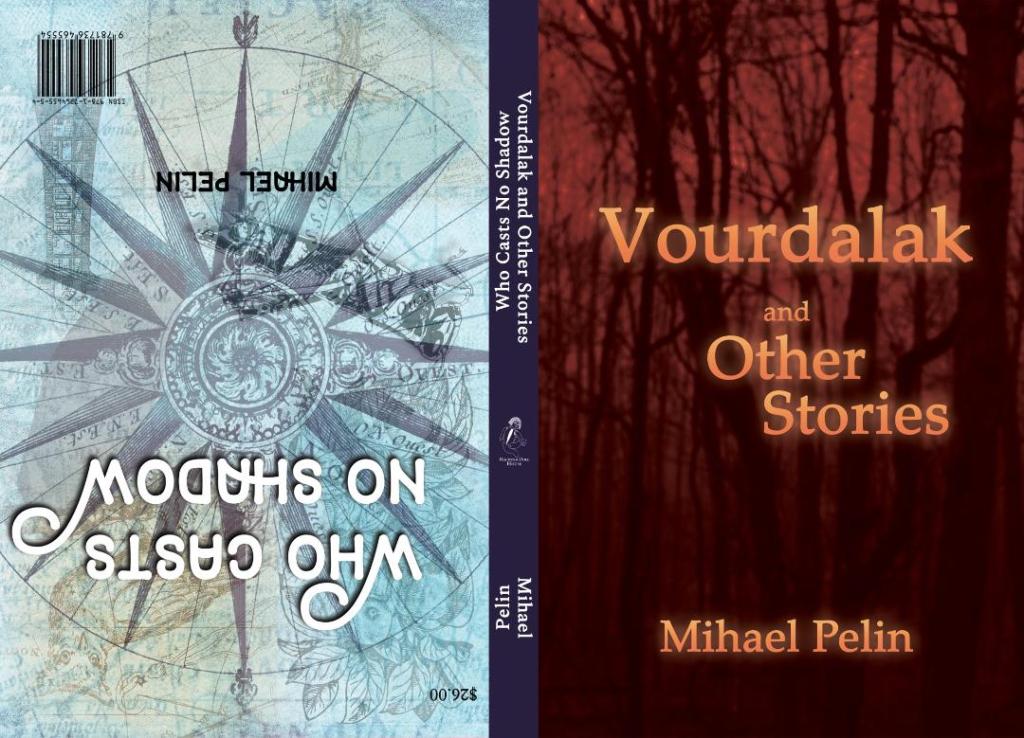

Hillary Leftwich recently had the chance to interview Mihael Pelin, author of Agape’s new release Vourdalak and Other Stories / Who Casts No Shadow.

HL: What are you reading these days? How do you feel about the work(s) you’re currently reading, and why?

MP: I am finishing up Anne Birrell’s translation of The Classic of Mountains and Seas as research for an upcoming project incorporating some mythical Chinese locales. The attempts on the part of westerners to extend the borders of their known world are as well-documented as they are fraught. It is interesting to see a record of how another culture, especially an ancient one, approached this same endeavor.

HL: What craft elements were you most interested in (or aware of) as you were writing and revising the different stories in Vourdalak and Other Stories? For example, your choices of perspective in the different stories felt very intentional, and really worked well to land me directly inside the narrators’ lives, or important life moments. Can you talk about this?

MP: I studied with the poet Diane Seuss, and one of the main things I took away from her instruction is the use of objects to convey inner states. I get very particular about the specifics of materials and objects, or the flora and fauna of the natural landscape, because to me there are a lot of ways you can make an inner world concrete with these kinds of details. It is more of a poet’s approach, or a cinematic approach, but that is what has worked for me.

Perspective is tricky in horror, especially because of how damaged your characters often are. For me it is about putting people as close as they can to such a character while having the story remain somewhat bearable. The crime fiction of Jim Thompson has been a good guide to this specific balance, though I absorbed some of my approach towards interiority in general from my reading of Joyce Carol Oates, who has drawn influence from horror fiction in her more literary work.

HL: Who/what are some of your writing obsessions that supported your creative process, or perhaps came to the surface for you, during the creation of Vourdalak and Other Stories? Why or how do you think those influences helped shape your work?

MP: More than one reader has noted my debt to Thomas Ligotti. As far as I am concerned, he is required reading for anyone who would attempt to bridge the gap between literary and horror fiction. I owe my understanding of how these modes can be joined to my reading of his work.

HL: What does it mean to you, and for you, to have your book published and your words out in the world?

MP: Honestly, I am still getting used to the idea. It hasn’t quite registered with me.

HL: What is something you would like to share with people about Vourdalak and Other Stories? What do you want everyone to know about it?

MP: Like many of the books I have treasured most, this book is not for everybody. Those unreconciled to the many difficult and tragic aspects of human experience might find an echo of their unease within its pages.

HL: The opening line of Who Casts No Shadow captures the mood of the story immediately: “Perhaps it is best to begin this narrative with an omen.” As readers, we feel everything that’s in this line resonating through the themes that the rest of the novella unpacks. Can you speak on the aesthetic decision you made to open the book this way? What were you hoping for this line to achieve for the story, or convey to readers about the world within the book?

MP: Initially, it was a practical rather than an aesthetic decision. For this novella, there was a considerable delay before the supernatural elements as such entered the narrative. I wanted to begin with the supernatural in some way, to telegraph the type of story the reader had in their hands, rather than just springing it on them later. This approach also tied into the theme of approaching the numinous through the natural world, which emerges in a number of my stories, but especially this novella.

HL: The text of Who Casts No Shadow abounds with historical themes and ancient rites for a variety of purposes. Is there a similar sense of ritual when it comes to your writing practice?

MP: I wouldn’t say so. I cannot say that I am a particularly disciplined writer with a regular creative schedule. There have been times in my life where I have lived in such a manner, but at this point I am spread thin with the various responsibilities of middle age.

Typically, I will start with a seed, usually a piece of folklore. In my limited free time, I approach this seed fairly intuitively, feeling around it in the dark, as it were, looking for what inspires the sense of the horrific in me. Eventually, I will have enough material that I can impose a sort of narrative on the images, or play upon symbolic resonances between sections of the piece. But it is all quite intuitive. My forebrain doesn’t come in until the end.

HL: Throughout Who Casts No Shadow, you write in a very historical/period voice. Was this difficult to write within this POV/voice, or does it come naturally to you? Were there any authors who write in a similar voice that inspired you?

MP: I like antiquated prose. I have read enough of it that such a voice comes naturally to me. Now, if I were to try to write in an extended contemporary voice, with contemporary slang or jargon, that would be more difficult, and I avoid it if at all possible. For the most part, the closest I get to a contemporary tone comes out of my reading of Donald Goines and Iceberg Slim, writers from the 1970s-era renaissance in African-American pulp fiction, who both exert a subtle but extensive influence on my work. Beyond this, I trace a lot of my influence, both in form and content, to the old pulp Weird Tales. My favorite of these is Clark Ashton Smith, who elected to write popular fiction for magazines when his poetry career fizzled out.

HL: Two of the main characters in Who Casts No Shadow write each other letters, which creates a mood I found reminiscent of that in Vincent Van Gogh’s letters — a kind of yearning, and an exploration of the self. Was this choice intended to show readers more of your characters’ emotional range? What attracted you to the epistolary?

MP: The explication of the characters’ emotional range was really an added benefit to a decision that ultimately arose from the needs of the plot. Getting Calvin to Stannard Island was crucial to me, because the development of that setting was one of the initial inspirations for the novella. Margreatha, however, really insisted on herself as a character, and the impetus behind expanding the letters from the single letter she sent in my first draft was to give her more space within the story. This was one of many inspired suggestions from my editor.

HL: The novella and short stories are all works of fiction, but most authors draw on material from their own lives too, even if their work is imaginative. Is this the case for you? If so, are there any ways in which writing about your life has changed the way that you view any of your lived experiences?

MP: Much of my childhood, and, increasingly, as much of my middle age as is possible, was and is spent walking through the forest. A childhood in rural America leaves you with a perspective that seems deeply foreign to what I have experienced of contemporary societal discourse. This background has led me to draw heavily upon my experience of the natural world for my work. There are also less pleasant aspects of my life that I have used fiction to examine. Fiction has been critical in obtaining closure and distance from these events.

HL: What was the most challenging aspect of writing Vourdalak and Other Stories and Who Casts No Shadow?

MP: I write in isolation. I don’t take in much modern media and am naive in some ways with regard to our broader societal conversation. My experience of society is in terms of my immediate communities within the city of New Orleans. The cosmopolitan nature of my home has obviated some of the difficulties that this approach might entail were I in a more monocultural region. However, I have been reliant on more informed readers for their understanding of contemporary sensibilities.

HL: What’s next for you?

MP: I’m looking forward to the responsibility of having a book in the world. I will be doing some readings and trying to get copies into local bookstores. It will be interesting to see what, if anything, resonates with readers.

—————————————————

Hillary Leftwich is the author of two books, Ghosts Are Just Strangers Who Know How to Knock (Agape Editions, 2023) and Aura (Future Tense Books and Blackstone Audio Publishing, 2022). She owns Alchemy Author Services and Writing Workshop, and teaches writing at several universities and colleges as well as Lighthouse Writers, a local nonprofit for adults and youth. She teaches Tarot and Tarot writing workshops focusing on strengthening divination abilities and writing. Her latest work can be found or forthcoming in The Sun, Santa Fe Writers Project, and The Rumpus. She lives in Denver with her partner, her son, and their cat, Larry.

Originally hailing from rural Northern Michigan, M. Pelin lives and writes in New Orleans.

Leave a comment